This month, the Jewish Book Carnival is hosted by the Prosen People. Check out their links!

This month, the Jewish Book Carnival is hosted by the Prosen People. Check out their links!

Archive for Sheryl Stahl

Great links to the Jewish Book blogosphere

TOKENS OF THE PAST

“Ghetto Gelt: smuggled out of Warsaw, Poland…circa 1980”. A white post-it, attached to a plain envelope containing a few frayed paper bills, one coin. A gift from a friend of the Frances-Henry Library who had taken a tour of our Rare Book Room a few days earlier. I open the envelope and carefully spread out the contents on my desk. My vision blurs, and for a split second I stop breathing. I am holding “money” printed by the Germans for the use of Polish Jews, in the Lodz Ghetto. My first thoughts: What did this money buy? For how long? The many hands that touched this money – which ones of them survived? Which ones didn’t? And now that we were given this gift, how can we ensure that they are made visible and become useful to our academic pursuits at Hebrew Union College?

I let Librarian sensibilities take over, and turn to Sheryl, our consummate cataloger, for help.

“Realia”, she determines, we’ll catalog them as artifacts. In our world, as Wikipedia explains, the term realia refers to three-dimensional objects from real life such as coins, etc., that do not easily fit into the orderly categories of printed material. They can be either man-made (artifacts, tools, utensils, etc.) or naturally occurring (specimens, samples, etc.), usually borrowed, purchased, or received as donation for use in classroom instruction or in exhibits.

Initial research yields a source that holds the details that will help us describe and place the money in its context: Jewish Ghettos’ and Concentration Camps’ Money (1933-1945) by Zvi Stahl (1990). The second chapter contains images identical to the paper money we now own, and the story behind the German decision to produce it. We now have the tools, and soon enough the objects are placed in protective envelopes and the record entered in our online catalog. They join items such as stamps, coins, photographs and playing cards that enrich our collection, presenting opportunities to touch, smell and make good use of tokens of our past.

Post script: the Lodz Ghetto money was presented to the library while I was away in Israel. During a visit with one of my uncles, Yaʻakov Refalovich, he presented me with a copy of his memoirs, hand-written by him, printed and bound by his grandchildren for his 80th birthday. One of the chapters in the books told the story of his survival in the Lodz Ghetto. Having been published in a limited edition, the book was placed in the Rare Book Room as well. A week before Holocaust Memorial day…and so it goes…

Yaffa Weisman

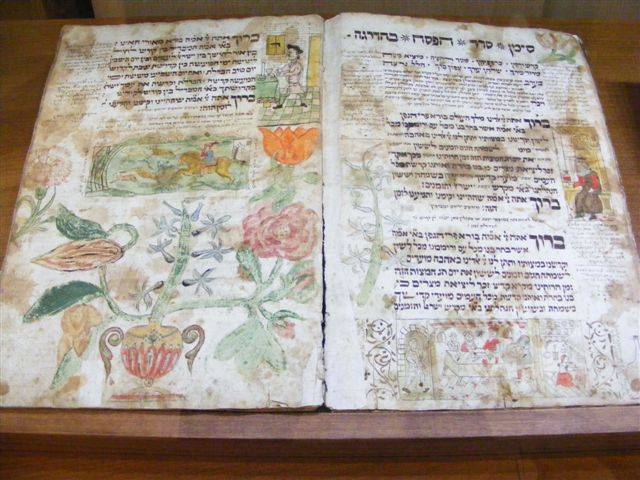

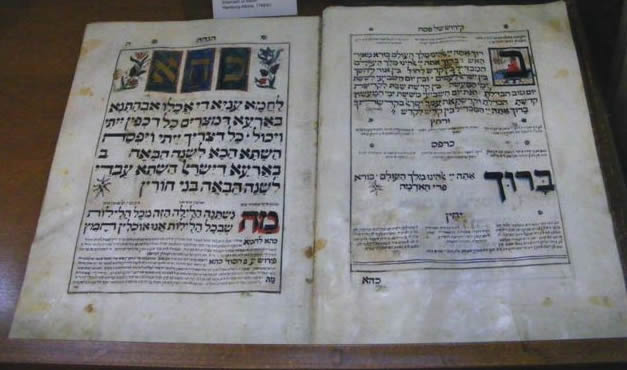

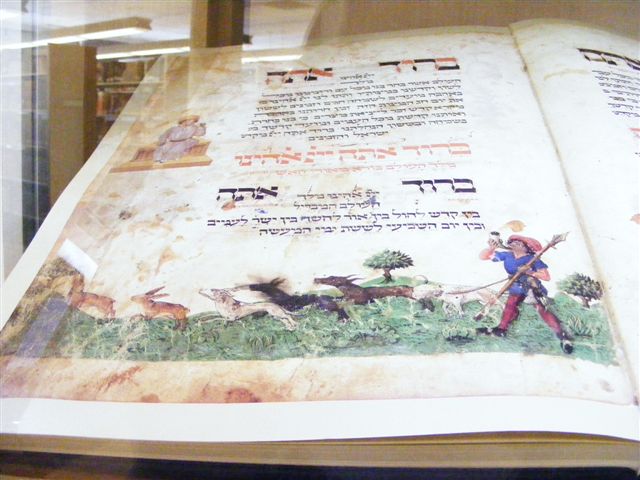

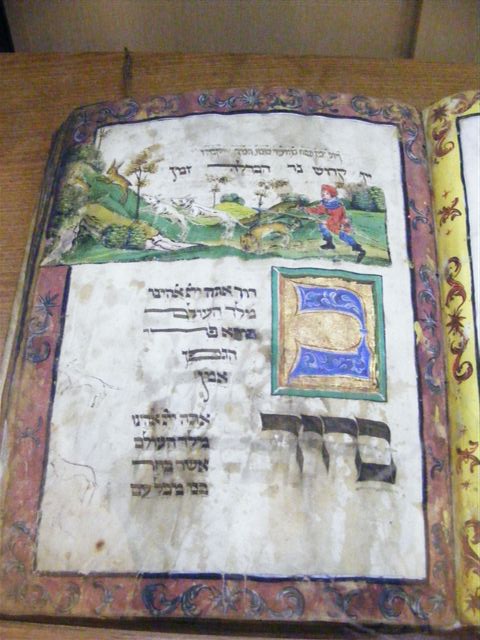

Hare Hunting in the Haggadah

Just why are there so many rabbit hunting scenes in early Haggadot? The Klau Cincinnati Library explores this question in their latest exhibit.

Just why are there so many rabbit hunting scenes in early Haggadot? The Klau Cincinnati Library explores this question in their latest exhibit.

The term YaKNeHaZ—also pronounced YaKN-HaZ—is an acronym composed of the initial letters of five Hebrew words: yayin, kiddush, ner, havdalah, zeman. It is a “seman,” a mnemonic aid to remembering the correct order of the blessings of the kiddush and the havdalah when Passover coincides with the conclusion of Shabbat. If we tum to the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Pesahim, 102b-103a, we learn that Abaye taught that the correct order for these prayers was YaKaZNaH; while Rabba maintained it was YaKNeHaZ, and the halachah is according to Rabba.

In the earliest manuscript siddurim and haggadot, including the Mahzor Vitri and the Seder Rav Amram Gaon, as well as the Birds Head Haggadah and the Kauffmann Haggadah, the seman YakNeHaZ appears either before or immediately after the kiddush and havdalah prayers. This practice of including this seman continued through the centuries in both manuscript and then printed haggadot, but began to disappear from printed haggadot in the nineteenth century

YakNeHaZ sounds similar to the German phrase “jag den Häs, hunt the hare.” At some time unknown to us, and most likely in a German- speaking region, an artist illuminating a Haggadah decided that the insertion of a hare-hunt scene at this point in the liturgy was a suitably amusing piece of artistic whimsy, a punning pictorial witticism.

We have no data that reveals exactly when some illuminator first inserted a hare-hunt scene in a Haggadah adjacent to the seman yaknehaz or the kiddush which includes the havdalah.

Indeed, the attempt to find some solution to this question is potentially clouded by the prevalence of hare-hunting scenes in the broad genre of European manuscript illustration and in the narrower area of Jewish illuminated manuscripts. From the pre-Carolingian era, the hare hunt was a recurring motif in European illuminated manuscripts. In one type of image, a dog or dogs chase a hare or hares. In another, individuals, armed with various weapons and accompanied by dogs, chase after a hare or hares. In one style the hunter holds a boar spear—a spear with a large head and a cross-piece to prevent a charging boar “running-up” the spear and goring the hunter with its tusks—which certainly seems to be ironic overkill when hunting a rabbit!

Hamburg-Altona. 1740/1741. Written and illuminated by Jankew Sofer ben Rabbi Judah Loeb, Shamash of Berlin.

In the Ashkenazi Haggadah, produced in the south of Germany around 1460 and illustrated by Joel ben Simeon Feibusch, there is neither liturgical direction nor seman; the illustration appears on the bottom of the page which contains the blessing for ner, and part of the havdalah. The image itself has come to represent the vocalization of the seman, that is “jag den Häs = YaKNHa”Z.”

First Cincinnati Haggadah. 15th century. In this famous example from the First Cincinnati Haggadah, produced in southern Germany towards the end of the fifteenth century, we see that the scribe, Meir ben Israel Jaffe of Heidelberg, has written the seman as part of his liturgical directions, and then "spelledout" the seman underneath as five words. Immediately under these words is the hare-hunt scene.

Like the Ashkenazi Haggadah, the Washington Haggadah was also illuminated by Joel ben Simeon. As is common in medieval Haggadah illustration, we see an armed man next to the beginning of the paragraph beginning “Tse, u-lemad, Go forth and learn what Laban the Aramean sought to do to Jacob our father. Pharaoh only decreed concerning the males; but Laban sought to destroy all, as it is written ‘An Aramaean destroying my father’. " If you look carefully, you will see that the drawing of a hare has been incorporated into the rubrication surrounding the word "va-yered'' beginning the very next paragraph. What we have here in the Washington Haggadah is a "hare hunt," with a hunter and a hare. The image of the armed man represents Laban, who is out hunting for Jacob, represented here by the rabbit hiding in the rubrication.

Moss Haggadah. When European Jews included hare hunt scenes in their Haggadot, I suspected that their sympathies lay with the hare! It seems to me that this apparently incongruous hare-hunting scene found its way into these European Haggadot precisely because it represented the image of the persecuted Jews. I became suddenly obsessed with images of hares and their relentless huntsmen. Then, at one point, my focus shifted from the human hunter of the hare to its natural predators. I caught a glimpse of a stark and powerful new image: that of the eagle. I began tracking down this bird of prey in zoology and mythology, heraldry and human history. I’ve collected some of these images on page 7b, adding only the hares which appear in the eagles’ clutches. … The last panel shows the hare which, always, somehow, manages to escape." —David Moss, A Song of David, Commentary

Barcelona Haggadah. The Barcelona Haggadah is a most exquisite fifteenth century work produced in the Catalan region of Spain. There are several different types of hound-hunter-hare vignettes that are depicted in this work. On the YaKeNHaZ page, one hound has caught sight of a hare, the other just sits there. On the facing page, in the bottom left, we see a rabbit emerging from the foliage; the rabbit seems to be chasing the dog. In the left panel, a dog with a hunting horn and a shield and dagger seems ready to do battle with a rabbit, armed either with a carrot or some sort of spear head. On the page following the kiddush for weeknight, at the bottom of the page, we see a hunter, with horn, and a staff from which seem to hang hares already caught. We also have a pack of hounds, and a hare.

Sarajevo Haggadah. Perhaps the single best known Jewish illuminated manuscript is the Sarajevo Hagadah, produced in Spain during the 14th century. We see here a hound chasing a hare, separated by the words "min ha'aretz." Turning back to the preceding page, we find the motivation for this image in the text, where the Egyptians plot the destruction of the Israelites: "... Let us, then, deal shrewdly with them, lest they increase, and in the event of war, join our enemies in fighting against us and gain ascendancy over the country." Egypt is the dog; Israel the hare. The phrase "gain ascendancy over the country" translates the Hebrew "ve-'alah min ha-'aretz,” which can be rendered literally: “And he sprang up from the earth." The hound takes off after the rabbit as it springs up from cover.

Some Roots of American Jewish Education

I am excited to share my conversation with Dr. Jonathan Krasner, HUC professor of the American Jewish Experience and author of The Benderly Boys & American Jewish Education.

SFS: Jonathan, congratulations on winning the National Jewish Book Award for American Jewish Studies!

JK: Thanks, Sheryl. It is very exciting!

SFS: I had not realized until I read your book, how big an impact Samson Benderly has made on my life and that of my children. In fact, I had never heard of him. But I suspect his fingerprints are all over the Jewish supplementary schools and camp that I attended as well as here HUC. Tell me about Benderly’s major works.

JK: Samson Benderly was a fascinating guy. Born into a Hasidic family in Safed in the late 19th century, he defied his parents and went to study medicine in Beirut and, later, Baltimore. In order to support himself he taught Hebrew and eventually became the head of a progressive supplementary school in Baltimore. Somewhere along the way he became one of the earliest Jewish educators in North America to teach Hebrew using the immersion method — Ivrit b’Ivrit. One of his earliest students was Henrietta Szold, who would go on to found Hadassah.

Over time, he realized that his sideline was actually his passion and he gave up medicine for education. News of his progressive methods and impressive results spread and he was called to New York to direct the first bureau of Jewish education. From his perch at the BJE, where he worked from 1910-1941, he worked to professionalize the field, modernize the supplementary schools, train teachers, develop curricula and teaching materials, open the first Jewish culture camps, and convince Federation that Jewish education should be a community responsibility. Most importantly, perhaps, he raised a generation of disciples who spread his ideas to communities across North America. They were known as the “Benderly boys.”

SFS: I was surprised that much of his early work focused on Jewish education for girls. Why did he think that was important and how did he make his programs so successful?

SFS: I was surprised that much of his early work focused on Jewish education for girls. Why did he think that was important and how did he make his programs so successful?

JK: Benderly’s interest in girls’ education stemmed from his conviction that the “future mothers of Israel” needed to have a strong Jewish foundation if they were to raise knowledgeable children with positive Jewish identities. Like many secular educators of his day, Benderly also believed that women’s dispositions made them better teachers, on average, than men, especially for young children. So he was very interested in preparing his most promising female students to become teachers. There was also some opportunism at play. Benderly wanted to open laboratory schools that would train teachers and pioneer modern methods. But he feared that parents would be hesitant to send their boys to these untested and newfangled institutions. Girls, on the other hand represented a terribly underserved market. With few alternatives, parents were more likely to “take a chance” with their girls. ( There was a further consideration that made girls’ education attractive: In those days, girls did not have bat mitzvahs, so the lab schools were under no pressure to teach to the test, so to speak.)

By the way, the “Benderly boys” included a number of girls! They received the same training as their male colleagues, studying at Columbia University Teachers College and the Jewish Theological Seminary’s Teachers Institute while interning at the Bureau of Jewish Education under Benderly’s mentorship. Most of these women followed the gender conventions of the day and eventually gave up their jobs to raise families. But a few stayed in the field. Libbie Berkson ran Camp Modin in Canaan, Maine for many years, and Leah Klepper taught pedagogy at the Teachers Institute.

SFS: Benderly worked largely with Jewish immigrants, especially in the early 1900’s. Immigrants often put much of their energy into assimilating and melting into the proverbial American pot. How did he entice them into incorporating Jewish education and religious (not just cultural) identity into their lives?

JK: Your question is very perceptive and points to one of Benderly’s greatest challenges. On the one hand, there were traditionalists who really wanted to give their children the same Jewish education they had back in eastern Europe. On the other hand, there were, for lack of a better term, assimilationists, who were far more concerned about making sure that their children fit in and succeeded in American society more generally. Benderly was promoting a third option, teaching an Americanized Judaism that was perceived to be in harmony with American culture and values and would not conflict with Jewish socio-economic aspirations. It was a struggle at first and there were many parents and community leaders who resisted. But as fears grew about an Jewishly alienated and godless second generation, more people began to embrace Benderly’s approach. As one Orthodox rabbi put it, Benderly’s methods might not be his cup of tea, but he seemed to get kids excited about Judaism, and that was worth the world. To be honest, however, Benderly’s modernized supplementary school only achieves universal acceptance in the postwar period when it becomes a standard feature of the suburban synagogue center.

SFS: The institutions that he created were very different from those of the European Jewish communities. What did Benderly feel was important for American Judaism?

JK: Benderly was an immigrant and he had the typical immigrant’s enthusiasm for America as a land of opportunity and a haven from intolerance. He was not interested in a strategy of resistance. Rather, he was an accommodationist. He thought Judaism could be harmonized with American values. But he also believed that it needed to be modernized in order to appeal to the younger generation. Benderly was also a cultural Zionist and believed that American Jewish culture could and should draw inspiration from the Jewish upbuilding of Palestine (Eretz Yisrael).

SFS: I was surprised to learn that Benderly was opposed to Jewish day schools. Why was that?

JK: Benderly realized that the vast majority of American Jews were wedded to the public schools. Secular education was a vehicle for socio-economic advancement and Americanization. So, his focus on supplementary education was based on practicality. It is important to remember that day school education did not really take off until the postwar era. At the same time, however, Benderly believed in the democratic mission of the public schools. So, there was also an ideological component to his opposition.

SFS: Jonathan, I have a question about your approach to this material. You mentioned that much of the previous scholarship on Jewish education was “prescriptive;” that it showed a top-down approach to what Jewish programs intended to do. You, however, wanted to be more “descriptive.” Can you tell me what that means to your research?

JK: Previous historians of Jewish education tended to also be practitioners. They had a vested interest in promoting a particular narrative. some were also sheepish about admitting the extent to which the educators’ aspirations went unrealized. they did not want to admit failure. I am certainly not dispassionate about my subject. But I think I have a level of distance that allows me to be more clear-eyed. I’ve also tried hard to supplement prescriptive materials — curricula, textbooks, articles — with descriptive sources — photos, internal reports, private correspondence. Taken together, I think they paint a more well-rounded picture of Jewish education in the first half of the 20th century.