The recent flare-up of violence at the Temple Mount (הר הבית, Har Habayit) reminds us yet again of the deeply religious aspects of the conflict in the Middle East. These have mostly to do, of course, with the disagreements between Jews and Muslims surrounding control over a site holy to both groups. But the word “religious” brings to mind another set of conflicts, namely the tensions, fissures, and battles that Israel’s capture of the Mount in 1967 have set off within Judaism itself. Most notably, possession of the Temple Mount has served to strengthen (or, depending on your point of view, to exacerbate) the messianic tendencies present in Zionism – in both its secular and its “religious” (Orthodox) manifestations – tendencies that have wide-ranging, deep, and potentially explosive implications for the future of the Zionist project. Tomer Persico tells the story quite nicely, and his blog is definitely worth a look.

The Temple Mount has had some fateful ramifications for Jewish law as well. In particular, it has in recent years become the cause of a major change – which one observer (see below) calls a “quiet revolution” – in the way Orthodox poskim (halakhic authorities) understand the halakhah. This blog, of course, is quite interested in the subject of halakhic change. Whether this particular change qualifies as “progressive” is another matter. But it is change, which as always teaches us something about the nature of the halakhah we study and try to live.

Our story begins with the Temple’s destruction in 70 C.E. As they reflected upon the place where the holy shrine had once stood, the Rabbis considered whether the site retained its sacred status. Their answer, generally, has been “yes”: Jewish legend holds that the Shekhinah (the presence of God) never departed from the Temple[1] or, to be more precise, from the Western Wall (הכותל המערבי), the last remaining visible structure of the Temple compound.[2] And from aggadah to halakhah: Rambam declares that the Temple Mount retains its status of sanctity (k’dusha) even though the Temple itself is no more.[3] Subsequent authorities, the rishonim and the aḥaronim (with one major exception),[4] follow this view.[5] The upshot is that today, since we exist in a state of ritual impurity (tumat met) that cannot be resolved without the proper sacrifices, we are forbidden to ascend the Temple Mount lest we traipse upon the spots that were off-limits to those in this condition.

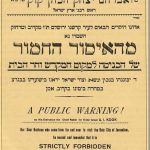

Such, at least was the state of Orthodox halakhic opinion until very recently. You can see this graphically illustrated in the two images at the top of this post. On the left is a “public warning” against entering the Mount issued by Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hakohen Kook (“Rav Kook,” d. 1935), the leading spiritual eminence of the Orthodox Zionist camp.[6] On the right is a similar prohibition (isur), dating from late summer of 1967, warning Jews in the strongest terms that by entering the Temple Mount they risk the Biblical punishment of karet (“death at the hands of Heaven”) for transgressing the precincts of holiness in a state of ritual impurity, a condition that cannot be remedied prior to the advent of the restoration of the proper purification sacrifices. The proclamation is signed by the two chief rabbis and by an impressive team[7] of Israeli Orthodox rabanim, a virtual Who’s Who among the leading poskim of the mid- to late-20th century (and beyond). And look closely – see the two arrows in the third column of the list? They mark the name of R. Zvi Yehudah Kook, the son of the great Rav and who until his death in 1982 was a major rabbinical leader of the Judea-Samaria settlement movement and contributor toward the messianic thrust of post-1967 Orthodox Zionism. Even he agrees that Jews are forbidden to enter the Temple Mount!

The signatories cite two major grounds in support of their isur. First, we no longer know the exact place of the Temple on the Mount, which means we can never be sure that in our impure state we are not transgressing the boundaries of k’dusha. And second, Jews are called upon to observe the mitzvah of mora hamikdash, awe and reverence for the Temple, an obligation that demands the greatest caution lest we violate its holiness. The consensus opinion among Orthodox authorities, indicated by that long list of prominent names, was that even now, in the wake of military victory and the messianic fervor that would follow in its wake, the prohibition against ascending the Temple Mount remains in place. Accordingly, for decades after the Six Day War, those Jews who visited the Mount tended to be non-religious, and in the main they did not hold prayer services there, whether out of lack of interest or out of deference to the sensitivities of the Muslims in charge of the site.

All of this, however, is changing. Reports in the Israeli press indicate that the number of Jews – Orthodox Jews, by the way – ascending the Mount has grown dramatically in recent years. The recent flare-up is intimately related to this trend, which shows no sign of abating. And more significantly for our purposes here, ascent of the Mount is gaining the approval of more and more Orthodox authorities. As noted recently by reporter Nadav Shragai (Hebrew):

Many hundreds of rabbinical judges and community rabbis, mostly associated with the Orthodox Zionist camp – including its mainstream – now either permit Jews to ascend the Temple Mount or do not prohibit them from doing so. We are talking about rabbis representing a wide spectrum of the Orthodox community, from Rabbi Hayyim Drokman, head of Yeshivat B’nei Akiva, the rabbis of the settler communities in Judea and Samaria, all the way to the rabbis of Beit Hillel who represent the “modern” and moderate stream of Orthodoxy. Even in the word of the ḥaredim there are those authorities who are beginning the break the “taboo.”

Shragai estimates the number of Israeli Orthodox rabbis who disregard the isur at 600. It is he who coined the term “quiet revolution” to describe this sea change in rabbinical opinion.

We do not wish to enter the halakhic specifics of this debate. Perhaps the growing number of Orthodox rabbis who ignore the prohibition believe that today we know for certain just where the holy places were located on the Mount, so that Jews might avoid those spots when they visit the place. Perhaps mora hamikdash, the reverence that observant Jews should show to the site of the Temple, isn’t what it used to be. All we know is that the prohibition decreed by centuries of p’sak and renewed by the great Israeli Orthodox poskim of the late 20th century has melted away in the face of the desire of observant Jews to ascend the Temple Mount and to daven there. Whether this desire, born of an increasingly messianic ideology in the Orthodox Zionist camp, is good or bad for the Jews is a matter of opinion.

But as a matter of fact, the new situation regarding the Temple Mount proves that the halakhah does change, that it responds to the religious, emotional, social and – yes, ideological – pressures of the age as reflected in the lives and the hearts of those who live by it. And that fact is what our own teaching and activity are all about. For when a community decides to reject the overwhelming consensus interpretation of the texts, a reading that has stood in place at least since the time of Rambam over 800 years ago, in favor of a new and different understanding, one that suits their values and their Jewish outlook… they are practicing the faith of progressive halakhah, a faith that holds that the texts and tradition of Jewish law need not be enslaved to old readings and consensus interpretations that no longer reflect our most basic religious commitments.

Moral of the story: although those 600 Israeli Orthodox rabbis presumably do not define what they are doing as “progressive halakhah,” that is what they’re doing. They are participating in our work, and we welcome them to it. Because in the end, whether or not we like the changes they introduce, their efforts help strengthen the awareness that halakhah is indeed “flexible,”[8] “dynamic,”[9] and capable of change. And that awareness is most certainly good for the Jews.

___________________________________________________________________________

[1] Midrash D’varim Rabah, Va’etchanan; Midrash Sh’mot Rabah, Sh’mot, par. 2:2.

[2] See Midrash Shir Hashirim Rabah, parashah 2, par. 4; Me’am Lo’ez, Psalms 46:7,

[3] Mishneh Torah, Beit Hab’ḥirah 6:14-16.

[4] Rabad, hasagah to Beit Hab’ḥirah 6:14.

[5] See the list compiled by R. Ovadyah Yosef in Resp. Y’ḥavei Da`at 1:25.

[6] See also his responsum Mishpat Kohen, no. 96, where he supports the prohibition is detail.

[7] Let’s put it this way: if one could draft a fantasy team in the NPL – the National Poskim League – we’d want these guys to be on ours. (Unless, of course, the league rules allowed us to draft progressive rabbis!)

[8] “אין גמישות כגמישותה של ההלכה” – “There is no ‘flexibility’ like that of the halakhah“; R. Hayyim David Halevy, Resp. Aseh L’kha Rav 7:54.

[9] Robert Gordis, The Dynamics of Judaism: A Study in Jewish Law. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990.