On Monday, August 21, 2017, folks living in a large swath of the United States will get to witness the exceedingly rare phenomenon of a total solar eclipse. (Please do it safely!) And, wouldn’t you know it, there’s a Jewish angle. Roger Price, the author of the always fascinating blog Judaism and Science, reminds us that Jewish tradition prescribes no b’rakhah (blessing, benediction) for one to recite upon seeing an eclipse. Which is at least a bit strange. After all, there is a blessing for one to say when witnessing a comet or lightning, or for beholding impressive natural sites like oceans or mountain ranges. There’s a blessing to recite upon hearing thunder and even for experiencing an earthquake. So why not for an eclipse? Continue reading A Blessing for an Eclipse?

The Mount and the Message

The recent flare-up of violence at the Temple Mount (הר הבית, Har Habayit) reminds us yet again of the deeply religious aspects of the conflict in the Middle East. These have mostly to do, of course, with the disagreements between Jews and Muslims surrounding control over a site holy to both groups. But the word “religious” brings to mind another set of conflicts, namely the tensions, fissures, and battles that Israel’s capture of the Mount in 1967 have set off within Judaism itself. Most notably, possession of the Temple Mount has served to strengthen (or, depending on your point of view, to exacerbate) the messianic tendencies present in Zionism – in both its secular and its “religious” (Orthodox) manifestations – tendencies that have wide-ranging, deep, and potentially explosive implications for the future of the Zionist project. Tomer Persico tells the story quite nicely, and his blog is definitely worth a look.

The Temple Mount has had some fateful ramifications for Jewish law as well. In particular, it has in recent years become the cause of a major change – which one observer (see below) calls a “quiet revolution” – in the way Orthodox poskim (halakhic authorities) understand the halakhah. This blog, of course, is quite interested in the subject of halakhic change. Whether this particular change qualifies as “progressive” is another matter. But it is change, which as always teaches us something about the nature of the halakhah we study and try to live. Continue reading The Mount and the Message

Tisha B’Av: A Partial Fast?

In advance of Tisha B’Av, the most somber day of the Jewish year, we consider the well-known position of the Conservative/Masorti movement declaring it permissible to end one’s fast on that day following the minḥah (afternoon) service. By ” minḥah” is meant minḥah g’dolah, the earliest time the service may be prayed. (The time for minḥah g’dolah in Jerusalem this year on Tisha B’Av – August 1, 2017 – begins at 1:19 pm.) The position is set forth in a t’shuvah of the Vaad Halakhah, or Law Committee, of the Israel branch of the Rabbinical Assembly (RA). The opinion, which expresses the Committee’s majority view, was authored by Rabbi Tuvia Friedman; Rabbi David Golinkin dissents, arguing that the full-day fast be maintained. (See here, in Volume One of the Vaad’s t’shuvot, for English summaries.) While the majority bases its argument upon a number of different considerations, we want to look here at the central part of its halakhic argument, found in section 4 of the responsum, “The Talmud and Its Commentators on Tisha B’Av.” Continue reading Tisha B’Av: A Partial Fast?

Who Defines “Authenticity”?

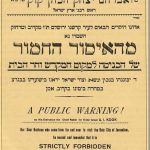

With the possible exception of Yom Kippur, no date in Israel’s national calendar is more solemn than Yom Hazikaron, the day of memorial for those who have perished in defense of the state since its founding. Like all national memorial days, its observance is marked by ceremonies and rituals that unite the citizens in mourning for the fallen. The most dramatic of these is the sounding of a siren throughout the land for a duration of one minute in the evening and two minutes in the morning, a signal that summons the entire population to stop whatever they are doing to stand in silent tribute and reflection. That drama, unfortunately, does not impress everybody. For example, there are ḥaredim who have never reconciled with the creation of the Jewish state. They refuse to participate in its national observances, and some of them pointedly do not stand in silence and do not interrupt their activities when the siren sounds. Continue reading Who Defines “Authenticity”?

The OU on Female Clergy, Part 2: Why the Texts are Insufficient

In our last post, we discussed last February’s decision of the “Rabbinic Panel” of the Orthodox Union (OU) prohibiting female clergy in the OU’s member congregations. That decision is accompanied by an extended essay in which the members of the panel, seven leading centrist[1] Orthodox poskim, set forth the reasoning behind it. The essay begins with a description of “halakhic methodology,” the way in which poskim are said to arrive at their decisions. We called that description “refreshingly honest” because it freely acknowledges the dominant role played by the “halakhic ethos” or “mesorah,” the halakhist’s ideological worldview, his sense of what an “authentic” interpretation of Torah would require, in the decision-making process. This is especially important in our case, because the legal sources, the halakhic texts upon which any rabbinical ruling is ostensibly based, are insufficient to answer the question whether women may serve as rabbis or other clergy.[2] Continue reading The OU on Female Clergy, Part 2: Why the Texts are Insufficient

The OU on Female Clergy: Some Refreshing Honesty

Last February 1, the Orthodox Union, the umbrella organization of mainstream Orthodoxy in North America, adopted as its official policy a rabbinical ruling that prohibits women from serving as clergy in any of its over 400 member synagogues. The intention, evidently, was to resolve the controversy over the ordination of women as “halakhic, spiritual, and Torah leaders” in the modern Orthodox community. That resolution, to put it mildly, has not yet occurred. Orthodox supporters of women’s ordination have denounced the ruling (here, here, and here) – one calls it “an historic mistake of epic proportions” – and seem determined to stick to their course. We’re obviously sympathetic, and we wish them success in resisting the OU’s policy.

But that’s not what this post is about. Continue reading The OU on Female Clergy: Some Refreshing Honesty

The Reform Movement and Israel: The Evidence of the Prayerbook

Many of us in the progressive halakhah camp make our denominational home in the Reform movement. So it’s appropriate at this season of Yom Ha’atzma’ut to consider the relationship of North American Reform Judaism toward the State of Israel. To be specific, we’re not talking about political issues, such as security policy, relations with the Palestinians and the Arab states and the like. Nor do we have in mind the always sensitive and often infuriating realm of religion-and-state policy, which includes the Israeli government’s response to the legitimate demands of its non-Orthodox citizens. Our inquiry here is more theological than political: how does the organized Reform movement understand the religious significance of the state of Israel? What, according to official Reform movement doctrine, is the significance of the establishment and the existence of the state as a matter of Jewish faith and belief? We’re hardly the first ones to ask these questions, which are addressed in numerous sources.[1]

For purposes of this blog, though, there’s no better place to look than in Mishkan T’fila, the current official prayerbook published (2007) by the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR). That’s because, like the traditional Jewish prayerbook (siddur), Mishkan T’fila is very much a text of halakhah.[2] While it is not a comprehensive work of systematic theology, the prayerbook reveals better than any other source the collective vision of the Reform rabbinate as to how Reform communities ought to organize their worship and express verbally the community’s vision of God, Torah, and Jewish experience. So at the approach of Israel’s 69th anniversary we ask: what does the American Reform[3] prayerbook have to say about Israel in general and about Yom Ha’atzma`ut in particular? Continue reading The Reform Movement and Israel: The Evidence of the Prayerbook

Selling Hametz: A Convenient Falsehood?

Pesach is coming. It is time, therefore, to have an honest talk about legal fictions. Continue reading Selling Hametz: A Convenient Falsehood?

Immigration and Jewish Law: The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Meeting of the Freehof Institute

The Solomon B. Freehof Institute of Progressive Halakhah marked its twenty-fifth anniversary at the convention of the Central Conference of American Rabbis in Atlanta this past March 21. As always, the meeting featured presentations by speakers on a chosen theme. This year, the theme was the very timely topic of immigration: what insights does Jewish law offer to liberal Jews seeking to influence, change, or critique the immigration policies of the counties in which they live? The presentations will eventually be available in written form at the Institute’s website. Continue reading Immigration and Jewish Law: The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Meeting of the Freehof Institute

Where the Buck Stops

Now that the majority party in the U.S. Congress has introduced its replacement for the Affordable Care Act – a “replacement” in the sense that it replaces federal insurance subsidies with a new form of individual tax credits – perhaps we should revisit the issue we addressed in our last post. There, we argued that, in the view of the halakhah, “the provision of affordable care to the entire community is very much the responsibility of the community itself, acting through its government.” The newly-proposed plan appears to take a major step away from that goal and for that reason must be judged deficient from a halakhic perspective. Continue reading Where the Buck Stops