Now that some time has passed since the horrific murders at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, it is appropriate that we turn our attention to one of the more disturbing public responses to that event: the outright refusal of Israel’s Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi David Lau to refer to Tree of Life as a synagogue. This, because Tree of Life defines itself as a Conservative congregation and because its building is home to several small, non-Orthodox congregations that worship there on Shabbat.

We will not bother here to excoriate the chief rabbi for his insensitivity and rank boorishness, his serving as yet another example of how some Jewish leaders prefer to fan the flames of divisiveness even at moments that so desperately call for unity. Instead, we think his remarks call for a brief and relatively uncomplicated shiur (lesson) in halakhah. The subject: what is a synagogue?

We begin with the p’sak (ruling) of Rambam in his Mishneh Torah, Hilkhot T’filah 11:1:

כל מקום שיש בו עשרה מישראל צריך להכין לו בית שיכנסו בו לתפלה בכל עת תפלה ומקום זה נקרא בה”כ, וכופין בני העיר זה את זה לבנות להם בה”כ ולקנות להם ספר תורה נביאים וכתובים.

1) Any locale in which ten Jews reside must set aside a building or room (bayit) into which they may assemble (yikansu) to pray at the set times for prayer. This place is called a synagogue (beit hak’nesset).

2) The members of the community may coerce each other to build a synagogue and to purchase a Torah scroll and other Biblical texts.

Notice that Rambam speaks here of two distinct issues. Paragraph 2) describes the power of the community to levy taxes for the building of a synagogue and the acquisition of the necessary liturgical texts. This rule is not original to Rambam. The source is the Tosefta (Lieberman ed. Bava Metzi`a 11:23), and Rambam’s great predecessor, R. Yitzhak Alfasi, has already cited it as authoritative halakhah (Hilkhot HaRif, Bava Batra, fol. 5a). The first paragraph, on the other hand, is original with the Mishneh Torah, for nowhere in the Rabbinic and earlier halakhic sources do we find this definition for a “synagogue”: that is, a “synagogue” is any structure that a congregation of ten Jews designates as such. The *beit k’nesset* (literally, “place of assembly”) acquires its status simply by the fact that the community assembles there to pray on a regular basis. Period; full stop; that’s all it takes to create a “synagogue.” Jews have been assembling to pray for many years at Congregation Tree of Life. Indeed, those who were gunned down on that awful Shabbat morning were among the most faithful members of its minyan. There can be no question, then, that Tree of Life where Jews is a synagogue according to halakhah.

This conclusion would presumably disturb the chief rabbi. He would respond that, even if Tree of Life were at one time a synagogue, it has lost that status due to the “sinful” activities conducted therein. After all, the congregation includes women in its minyan and acknowledges that their ritual status equals that of men. This, in the chief rabbi’s eyes, invalidates the prayer services at Tree of Life; one does not fulfill one’s halakhic obligation to pray by davening there.

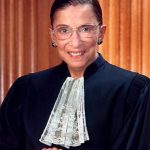

Really? We will not bother here to rehearse the halakhic arguments in favor of women’s full and equal participation in Jewish ritual life. Suffice it to say that, even if the chief rabbi does not find those arguments convincing, there exists a real dispute (maḥloket) within the halakhic community over the question. Our point, though, is that even were we to grant the chief rabbi’s assertion that the t’filah at Tree of Life is somehow a transgression and a sin – which we don’t – that still would not alter the status of the place as a synagogue. Our authority for this claim is none other than R. Moshe Feinstein, who famously ruled that once a synagogue has been established and has served as a place of communal prayer, it does not lose its sanctity even if “sinful and scandalous acts” have taken place on the premises אלא ודאי דהקדושה שנעשה בביהכ”נ אינה יורדת שוב אף שלא מתנהגים שם בקדושה ואף כשעושים שם עבירות ועניני קלון (Resp. Ig’rot Moshe, Oraḥ Ḥayyim 1:46). It’s clear from R. Moshe’s discussion that the “scandalous acts” of which he speaks are a lot more scandalous than, say, a woman being called to the Torah – and yet, despite that sinful behavior, the place retains its sanctity and remains a synagogue.

No, we do not expect the chief rabbi to acknowledge the halakhic validity of the prayers uttered at Tree of Life. And we don’t imagine that he’ll be davening any time soon there or at any other non-Orthodox house of worship. We recognize that he, no less than anyone else, deserves his freedom of conscience and religious expression. But that freedom does not give him the power to declare that Tree of Life, or for that matter any particular structure that Jews use for prayer, is somehow not a synagogue. To repeat: Tree of Life is a synagogue because a community of Jews has designated it as such. The halakhah acknowledges their act as valid, even if the chief rabbi will not.

Their honor, and the memory of those who died on that terrible Shabbat in sanctification of the divine name, demand that the chief rabbi apologize. Failing that, maybe it’s best that he keep silent.