Pesach is coming. It is time, therefore, to have an honest talk about legal fictions.

Let’s define a “legal fiction” as an assertion by a court or other legal institution that a particular fact or set of facts is true when it is plainly false. The court will resort to this fiction because it does not wish to be seen as changing a legal rule, which is something that courts are usually not empowered to do.[1] Judges, after all, are supposed to apply the law and not to change it. The problem, of course, is that sometimes the law really does need to change, for example, if the application of a rule of law will lead to unjust or undesirable results in particular cases. So “it has long been considered more acceptable in the pursuit of justice… to re-describe the facts in order to achieve the right result than to rewrite a law in order to do the same thing,” even if, in reality, there’s little difference between the two.[2] The author of the classic study notes that, because law is a conservative discipline, the court is frequently unable to declare what it is really doing and to take the most direct route to its favored result. Instead, it must sometimes introduce a change into the law in the guise of the old law so as “to temper the boldness of the change.” That’s not necessarily a bad thing. After all, it’s a change that is necessary, and none of us – neither the judge nor those who read the judge’s decision – are fooled by the court’s fiction. We all know what is going on. For this reason, the author concludes, the legal fiction “is distinguished from a lie by the fact that it is not intended to deceive.”[3]

But still, even in the absence of actual deception, the legal fiction remains a fiction. The fact that the law must speak a falsehood, even to good purpose and even though everybody knows it’s a falsehood, ought to be a source of at least some discomfort to all those who value the truth.

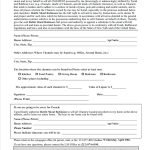

Perhaps the most obvious example of a fiction in Jewish law is the practice of selling ḥametz prior to Pesach. The householder, commanded to remove all ḥametz from his or her legal possession before the onset of the holiday, sells those foodstuffs to a non-Jew. In most cases, individuals authorize the rabbi of the community to act as their agent in the sale, and it is the rabbi who sells the ḥametz to the non-Jew. (And of course, since it’s 2017/5777, you don’t need a community rabbi; you can do it online!) But it is obvious to all involved that, while the sale is a valid and binding one – it meets all the formal requirements of acquisition (kinyan) under Jewish law – it is not ultimately an honest one: both parties know that the Gentile will sell the ḥametz back to the Jew once Pesach ends. Indeed, the buy-back usually takes place a few minutes after havdalah at the conclusion of the festival, after which time Jews are permitted to consume the ḥametz that has remained in their homes (though not “owned” by them) throughout the holiday. This eminently transparent evasion of the law is rooted in the Torah’s demand (Exodus 12:15) that “you shall remove leaven from your houses” before the festival begins. The word translated here as “remove” – תשביתו, tashbitu – does not specify just how to get rid of our ḥametz. As we read in the CCAR’s responsum[4] on the subject,

Some early Rabbinic authorities interpret the word tashbitu as “nullification,” an act by which the householder mentally renounces all ownership of the ḥametz.[5] The Talmud, too, declares that “according to Torah law, a simple act of nullification suffices” to remove ḥametz.[6] According to this view, the practices of b’dikat chameitz, the search for leaven conducted on the night before the seder, and biur ḥametz, the burning or other physical destruction of the leaven the next morning, are requirements of Rabbinic law,[7] instituted perhaps in order to prevent against the possibility that one might accidentally eat some of the ḥametz stored in one’s home during the holiday. Other commentators disagree. In their opinion, the Torah requires biur, the physical removal of ḥametz, as well as its nullification. Indeed, they hold, the requirement of tashbitu is fulfilled primarily through biur. If, as the Talmud says, “nullification suffices,” this may refer to ḥametz in one’s possession that one does not know about and therefore cannot burn or scatter.[8] A third interpretation is that the Torah itself permits the “removal” of ḥametz in either manner, through nullification or through physical destruction; the Rabbis, however, instituted the requirement that both procedures be performed.[9]

When a Jew owns a great deal of ḥametz, the physical destruction of those foodstuffs – biur ḥametz – becomes impractical. Hence the device of m’khirat (sale of) ḥametz, a medieval development upon a Talmudic source.[10] The sale is a valid way to “remove” the ḥametz because it is g’murah, unencumbered, with no strings attached; the Jew has no valid legal claim to the foodstuffs now in the Gentile’s possession. Except, of course, that in reality the Jew has every expectation that the Gentile will return the ḥametz to him or her at the conclusion of Pesach.

The CCAR responsum makes a strong argument that the sale of ḥametz is too fictitious to deserve the respect of contemporary liberal Jews. It proposes instead that, should one own too much ḥametz to comfortably destroy or give away, one favor the process of bitul ḥametz, the nullification of ḥametz, which as we have seen is well-supported in the sources as the means of fulfilling the Torah’s mitzvah. True, bitul is vulnerable to similar objections: when we “nullify” the ḥametz in our possession (but know that we will re-acquire it at the end of the festival), is our intention any less fictitious than when we sell it to a non-Jew? The answer, it would seem, is that if bitul is all that the Torah actually requires, then by definition it suffices to fulfill the mitzvah, and we need not add to it a procedure (i.e., sale) that is fictitious from the get-go. Besides, as the responsum points out, bitul is something we can perform ourselves. It’s more than a bit demeaning, come to think of it, for us to concede that we cannot fulfill our own ritual requirement in the absence of a non-Jew’s collaboration in what amounts to a transparent legal sleight-of-hand.

The responsum should also get us to rethinking the place of legal fictions in the halakhah. One can well argue that fictions perform a vital and necessary role in a legal tradition in which it is next to impossible to re-write the law of the Torah, to enact new legislation that corrects the defects of existing law. (We’ll leave for a future comment the possibility that rabbis and their communities might resort once again to the process of takanah, of enacting legislation that is indeed aimed at correcting such defects.) Legal fiction, in this view, is simply the homage we pay to two conflicting goals: in this case, the Torah’s requirement that we get rid of our ḥametz and the Torah’s desire to spare us from undue financial hardship.[11] We wish to achieve both these ends; we cannot alter the law regarding possession of ḥametz, and so legal fiction is the only way we simultaneously honor the law while acknowledging economic reality. On the other hand, to the extent that we value honesty over subterfuge, the legal fiction ought to be regarded with deep suspicion. If rabbis can’t (or won’t – there’s a big difference) take steps to remove the element of deception (however necessary it may be) from the halakhah, there is a good case to be made for preferring the halakhic option that is transparent and straightforward and that avoids unnecessary fictions.

So… since Pesach is coming… you might want to sell your ḥametz, just to be on the safe side. There are many worse things in this world than maintaining a time-honored Jewish custom, even if that custom is a legal fiction. But if you like your halakhah straight, with a minimum of “lies not intended to deceive,” you might want to consider the CCAR responsum, nullify your ḥametz, and put it out of reach until the festival ends.

Ḥag sameaḥ v’kasher.

__________________________________________________________________________

[1] See Peter J. Smith, “New Legal Fictions,” Georgetown Law Journal 95 (2007), pp. 1435-1495, at p. 1437.

[2] Frederick Schauer, “Legal Fictions Revisited,” at p. 19. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1904555 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1904555.

[3] Lon L. Fuller, Legal Fictions (Stanford, CA: Stanford U. Press, 1967), at pp. 58 and 6.

[4] The CCAR Responsa website is fully accessible only to members of the Central Conference of American Rabbis. If you’re not one of those rabbis, make friends with one and she or he will get you the material! In the meantime, would it kill you to buy the books, in printed or PDF format, from the CCAR Press? This particular t’shuvah is found in Reform Responsa for the Twenty-First Century, vol. 1 (New York: CCAR, 2010), pp. 65-76.

[5] The classic Aramaic Targumim – Onkelos and Yonatan – do just that, translating the word tashbitu as תבטלון, “you shall nullify.”

[6] B. P’sachim 4b. Rashi, s.v. bevitul be`alma, explains this rule on the grounds that the Torah does not say tevaaru, “burn the ḥametz” but rather “remove” (tashbitu) it, which may be done by “removing” it from our consciousness. Tosafot, P’sachim 4b, s.v. mid’oraita, disagrees, on the basis of Talmudic evidence that tashbitu is understood as physical destruction. Nonetheless, Tosafot holds that “nullification” is sufficient under the terms of another verse: Exod. 13:7: you may not “see” your own ḥametz, but you are permitted to see ḥametz owned by others or that is ownerless (B. P’sachim 5b).

[7] Rambam, Mishneh Torah, Hil. Ḥametz Umatzah 2:2-3, according to our printed versions and the Kafaḥ manuscript edition.

[8] Rambam (preceding note), according to the version preserved by R. Yosef Caro in his Kesef Mishneh commentary.

[9] This approach is characteristic of the “Ramban school”; see R. Nissim Gerondi’s commentary to Alfasi, P’sachim, fol. 1a.

[10] The source is Tosefta P’sachim 2:6, which speaks of the special case in which a Jew is on board a ship. The sale of ḥametz turns this special case into a regular rule.

[11] התורה חסה על ממונם של ישראל; B. Ḥulin 49b.