The United States Congress is struggling – again – over the future of the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or “Obamacare”) of 2010. As Jewish organizations weigh in on the debate, the question will inevitably arise: what does Jewish tradition, and specifically the halakhic tradition, teach us concerning the role of the government in the provision of medical care in a modern democratic society? And that, of course, is a difficult question to answer. We know that the halakhah, based in sources that reflect a social, economic, and political context quite different from our own, does not speak with precision to most of the particular issues our society confronts today.[1] To put this differently: on its face, the halakhah doesn’t tell us whether the ACA should be retained, repealed, or amended. On the other hand, Jewish law does contain some important basic teachings about the nature of the good society that can and ought to guide our thinking on public questions. Yes, we have to resist the temptation of learning too much detail from broad, general statements in the texts. We’ve discussed that problem on this blog. But there are occasions when the tradition actually gives us enough practical detail, if not to answer our questions precisely, then at least to point the way for our thinking. And the issue of national healthcare policy is one of those occasions. Continue reading On Medical Care, Mitzvah, and Public Responsibility

All posts by Mark Washofsky

Sefarad – A Different Halakhic World?

Rabbi Haim Amsalem is a “Sefardi”[1] political activist in Israel. (We’ve met him previously on this blog.) One of the founding members of the ḥaredi Shas political party, he was expelled in 2010 in large part due to his dissent over the halakhic policy of the Sefardi rabbinical establishment (rabanut) dominated by then Chief Rabbi Ovadyah Yosef and his sons. His major complaint was and is that the Sefardi rabbinate has adopted the extremist, stringent approach to p’sikah (halakhic decision) characteristic of the Ashkenaic ḥaredim at the expense of the classic – and much more moderate – Sefardi tradition. For his temerity, Amsalem has been branded a “Reformi,” which is just about the worst thing an Orthodox Jew can call another Jew.[2] Not to be outdone, Amsalem strikes back in kind: it is the Sefardi rabanut, he claims, that is actually doing the work of the Reformers.[3] He explains that it was the Asheknazi Orthodox rabbinate that actually created the Reform movement in 19th-century Europe through its narrow, sectarian, and rejectionist p’sikah that drove millions of Jews away from Torah and tradition. And the Sefardi rabbinate in Israel today is making the same mistake, “creating” Reform Jews through its slavish imitation of the halakhic method of the “Litvaks.” Continue reading Sefarad – A Different Halakhic World?

The Get from Safed

It’s a story, of hope and tragedy. The hope lies in the fact that some rabbis are capable of creative halakhic thinking to bring relief to those who suffer under the law’s inequity. The tragedy is that they aren’t the only rabbis in this story. Continue reading The Get from Safed

The New Modern Orthodox Platform

The Rabbinical Council of America (RCA) is the largest association of rabbis who profess a “Modern Orthodox” outlook. Recently, the RCA decided that it was time to adopt a statement of principles, entitled “Raising the Banner of Modern Orthodoxy,” which the organization describes as “A Proud Platform for Modern Orthodoxy for the 21st Century.” The platform takes on the increasingly difficult task of defining the “Modern Orthodox” position in the face of challenges from two sides. Looking to its right, the RCA wishes to distinguish its Judaic outlook from that of the ḥaredi or “ultra” Orthodox sects that consciously reject most sorts of accommodation with the culture of modernity. And looking to its left, it seeks to define itself against so-called “Open Orthodoxy,” which declares its loyalty to Orthodox halakhah while advocating an even more “open” posture toward contemporary cultural values, particularly regarding the expansion of women’s participation in public religious life. Hence, the pressing need for a platform to spell out in detail the RCA’s version of Modern Orthodoxy.[1]

How successful is the platform in accomplishing its goal? To our decidedly non-Orthodox way of thinking, the text strikes a welcome note of moderation. “Reflecting upon how frequent and tragic schism has been in the history of our people,” the document calls upon Modern Orthodox Jews to engage “in constructive religious debate that is ‘for the sake of heaven’ by defending our opponents’ honor and motives; by emphasizing points of accord as much as areas of dissent; and, by seeking truth with grace, civility, and love.” In a religious (not to mention political) environment too often poisoned by the rhetoric of extremism (here’s just the latest example), the RCA calls upon the members of its community to think carefully about the tone of their speech. That’s a message that all of us could (and obviously should) take to heart. Also positive is the platform’s call for Jews to comply “punctiliously” with non-discriminatory state legislation (“in fulfillment of the halachic requirement of dina de’malchuta dina“) and to pursue “knowledge of the sciences and humanities in order to know God’s Creation.” These statements sound pedestrian to progressives, but within the world of Orthodoxy they’re a certified big deal, a forthright repudiation of some of the more disagreeably parochial and obscurantist elements of far-right Orthodox culture.

Railroad, Part Two: Is the Halakhah Ready for Prime Time?

Does this man look like a progressive halakhic thinker to you? Not to us, either. But looks can be deceiving. Continue reading Railroad, Part Two: Is the Halakhah Ready for Prime Time?

Working on the Railroad: Observing Shabbat in a Jewish State

The latest battle in Israel’s Shabbat wars is more than the usual case of political infighting, though it is certainly that. Israel Railways wants to schedule repair work to its lines on Shabbat, when the trains don’t run, in order to avoid painful disruptions of service during the week. The prime minister, dependent on the support of ultra-Orthodox parties for his Knesset majority, bowed to their demand that the repair work be banned on Shabbat. To be fair, the ḥaredim do have tradition (and not only halakhah) on their side. For the railroad to undertake this work would violate Israel’s religious status quo, an informal yet historic arrangement (it has its own poorly-footnoted Wikipedia article) that determines just which public institutions are allowed to function on Shabbat. So you could say that it’s the railroad and not the ultra-Orthodox parties that touched off this particular fracas. On the other hand, while the status quo may have served well in the past as a good ceasefire agreement in the Shabbat wars, there’s nothing necessarily sacred about it; it’s been broken frequently, and by both sides. The railroad controversy might therefore be a good opportunity for Israelis, as well as for all who care about the nature and place of Jewish religion in the Jewish state, to come up with a better solution. Continue reading Working on the Railroad: Observing Shabbat in a Jewish State

Believing in Science

“More than 100 Nobel laureates are calling on Greenpeace to end its anti-GMO campaign.”

Headlines like that one sure do catch the eye. The scientists signing the letter urge the environmental organization Greenpeace to drop its opposition to genetically modified organisms (GMOs). In particular, they criticize Greenpeace’s efforts to block the development of Golden Rice, a genetically-modified strain of rice that is especially rich in beta carotene. (The hope is that the consumption of Golden Rice will help reduce Vitamin A deficiency and the resulting blindness among children in developing countries.) This is but the latest round in the ongoing battle over GMOs between the scientific community and those environmentalists who warn of any number of risks, often unspecified, posed by the technologies of genetic engineering and enhancement. The scientists say that Greenpeace doesn’t know what it’s talking about. Greenpeace, for its part, isn’t budging. Continue reading Believing in Science

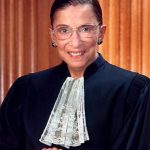

A Supreme Court Justice and a Rosh Yeshiva on the Art of Halakhic Decision

The ruling handed down this week by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, already being described as “the most significant victory in a generation” for abortion rights, raises some interesting parallels with halakhah. One of these, of course, is the substantive issue: does halakhah permit abortion and, if so, under what circumstances? We’ll address that important and complex question in a forthcoming post. But right now we’re focused on the matter of process. It turns out that, for all the differences between American law and Jewish law, the two systems display some interesting similarities in the way decisions are made. No big surprise there. Both legal traditions express themselves in the form of written texts, and those texts must be interpreted so that they can yield new meanings and speak to the cases and questions that arise every day. Lawyers and rabbis, in other words, share much the same interpretive task. And two comments by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her concurring opinion in Whole Woman’s Health offer insight into the way in which judges and poskim alike should think about doing their jobs. Continue reading A Supreme Court Justice and a Rosh Yeshiva on the Art of Halakhic Decision

Does Jewish Law Recognize the State of Israel? Part 2

Our last post discussed the troubling fact that the leading Orthodox poskim (halakhic authorities) define the law and legal system of the State of Israel as “foreign” or “Gentile law” (ערכאותיהם של גויים). To say that halakhah does not recognize the legitimacy of Israel’s law is to signal to observant Jewish citizens of the state that they may be entitled to violate that law. It is also to suggest that the state itself, which expresses its national identity and conducts its public life by means of its law, is a “Gentile” creation, neither truly “Jewish” nor totally legitimate in the eyes of the Torah. It is an embarrassment to the Zionist idea, an insult to all who would like to believe that there is no essential contradiction between the establishment of a modern, democratic Jewish state and the precepts of traditional Jewish religion.

It is also wrong. Continue reading Does Jewish Law Recognize the State of Israel? Part 2

Does Jewish Law Recognize the State of Israel?

As we celebrate Yom Ha’atzmaut 5776/2016, we turn to an old question about Jewish law and political sovereignty: does halakhah, traditional Jewish law, provide for the existence and functioning of the modern Jewish state of Israel? We don’t have in mind here the fundamental issue of whether traditional Jewish law permits the Jewish people to form a sovereign political entity prior to the coming of the Messiah. We’re talking rather about something more mundane but no less essential: does halakhah recognize the legitimacy of Israel’s law and legal system? Continue reading Does Jewish Law Recognize the State of Israel?