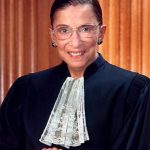

The ruling handed down this week by the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, already being described as “the most significant victory in a generation” for abortion rights, raises some interesting parallels with halakhah. One of these, of course, is the substantive issue: does halakhah permit abortion and, if so, under what circumstances? We’ll address that important and complex question in a forthcoming post. But right now we’re focused on the matter of process. It turns out that, for all the differences between American law and Jewish law, the two systems display some interesting similarities in the way decisions are made. No big surprise there. Both legal traditions express themselves in the form of written texts, and those texts must be interpreted so that they can yield new meanings and speak to the cases and questions that arise every day. Lawyers and rabbis, in other words, share much the same interpretive task. And two comments by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her concurring opinion in Whole Woman’s Health offer insight into the way in which judges and poskim alike should think about doing their jobs.

The case involved a series of strict medical regulations imposed by the state of Texas upon abortion clinics operating within its borders. The Court majority struck down the rules, finding that they posed a constitutionally-impermissible “substantial obstacle” to a woman seeking an abortion. The difficulty, of course, is how to define (i.e., to interpret the phrase) “substantial obstacle.” The state argued that the intent of the legislation was “to protect women’s health.” And while it might seem obvious that the real intent of the law was to force the closure of many abortion clinics, the state did have a point. Protection of the public health is, after all, a duty of the state government. Perhaps the medical hazards of the abortion procedure demand strict legal supervision, even at the cost of restricting access to abortion. And perhaps that decision is one for the state of Texas – and not for nine eight unelected judges to make. This is where Justice Ginsburg’s comments come into play. On the second page of her concurrence she writes:

Given these realities [i.e., that medical authorities declare abortion to be “at least as safe as other medical procedures routinely performed in outpatient settings” – ed.], it is beyond rational belief that (the legislation) could genuinely protect the health of women, and certain that the law “would simply make it more difficult for them to obtain abortions.”

And again:

When a State severely limits access to safe and legal procedures, women in desperate circumstances may resort to unlicensed rogue practitioners, faute de mieux, at great risk to their health and safety.

That is to say, when interpreting the meaning of a legal text the judge must be guided not simply by dictionary definitions and formal rules of hermeneutics but by wisdom, prudence, and common sense. These tools will help her discern the true purpose behind the text. And they require that she consider not only the abstract, logical reading of the law but also the real-world consequences of her decision. It is often possible to construe the words on the page in various ways. But the judge must consider just how this construction or this interpretation will affect the lives of the flesh-and-blood human beings who will have to live with it.

The same goes for the work of the posek, the halakhic decision maker. We find a powerful expression of this truth in the words of a noted Israeli authority, Rabbi Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch, the rosh yeshiva (head) of Yeshivat Birkat Moshe in Ma’ale Adumim. Rabbi Rabinovitch, the author of an important new commentary on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah,[1] has also distinguished himself as the head of a beit din (rabbinical court) currently challenging the Chief Rabbinate’s monopoly over (and stringent rules for) conversions in Israel. In a recent collection of his essays, he describes the activity of halakhic decision as follows:[2]

In addition to all that is written in the Torah, one must perceive the direction to which the Torah leads, the purpose (תכלית) it sets for human beings. The study of Torah causes some to fear the prospect of independent thought by way of common sense (sekhel yashar). But we need not seek an answer to every question in the form of a written text or a passage in the Shulchan Arukh. It is our duty always to think by way of common sense, seeking to know what the Torah commands, what purpose it sets for us, and how to act in such a way that our deeds lead us to achieve that desired purpose. All of this is true of the study of Torah and of the fulfillment of the mitzvot. It applies to the ritual mitvot and even more so to the ethical mitzvot, for matters of human relations by their very nature cannot be decided solely by resort to the written text. Rather, they are to be decided as well by common sense, a capacity nourished by a perceptive, sensitive, and honest mind.

Halakhah, Rabbi Rabinovitch teaches us, is too big, too deep, and too important to be restricted to the confines of the written text. Those who presume to speak in its name must do so with a careful eye toward the תכלית, the ultimate goal and purpose of the law, as well as to the formal logic of its words. And his remarks concerning the nature of the ethical mitzvot (המצוות שבין אדם לחבירו) remind us that p’sak (halakhic decision) has to be rendered with perception, sensitivity, and honesty – which is to say that the posek must show an awareness of and take responsibility for the effects of his ruling upon real people, upon human beings seeking to navigate the complex stream of life in an imperfect and challenging world.

Again, the obvious differences between these two traditions of law should not blind us to the similar challenges confronting those in either system who are tasked with interpreting the law, not simply as a classroom exercise but as a means of achieving the law’s underlying purpose. The words of Rabbi Rabinovitch may differ in form and style from those of Justice Ginsburg. But in their substance they point to the same end, the same takhlit. These two sages, both speaking from within the context of their own tradition, instruct us that decision making is product of experience as well as of logic, of the sensitive heart as well as the deductive mind, more an art than a science. Would that all judges and all poskim learn the lesson they teach us.

____________________________________________________________________

[1] The commentary is entitled יד פשוטה (Yad P’shutah), published by Ma’aliyot, Ma’ale Adumim, 1987–.

[2] נחום אליעזר רבינוביץ, מסילות בלבבם (מעליות, מעלה אדומים, 2015), עמ’ 21. The Hebrew text is as follows:

בנוסף לכל מה שכתוב בתורה צריך להבין גם לאן התורה מובילה ומה התכלית הנדרשת מן האדם. יש כאלו שלימוד התורה גורם להם לפחד מחשיבה עצמאית בשכל ישר. לא לכל דבר צריך לחפש סעיף מפורש בשלחן ערוך ואת האות הכתובה. נדרש מהאדם לחשוב תמיד בשכל ישר, מה התורה מצווה ומהי התכלית הנדרשת, וכיצד ליישם את התורה באופן נכון על מנת שהמעשים יובילו לתכלית הרצויה על פי התורה. הדברים אמורים הן בלימוד התורה והן בקיום המצוות. הדברים אמורים במצוות שבין אדם למקום, ועוד יותר במצוות שבין אדם לחבירו, הואיל ויחסי אנוש, מעצם טבעם, אינם יכולים להיקבע רק לפי האות הכתובה, אלא יש להכריע בהם גם לפי השכל הישר הנובע מלב נבון ומבין, מרגיש וישר